From the Item Bank |

||

The Professional Testing Blog |

||

Debunking a Few Myths About CertificationFebruary 4, 2016 | |“Many people take offense when the narratives they believe to be true are called myths,” Wikipedia explains. “This usage is frequently associated with legend, fiction, fairy tale, folklore, fable, confusing data, personal desire and urban legend,” and for some of us, certification practices. This is the first of a series in which we hope to debunk some of the more popular myths surrounding certification practices, and provide you with some strategies that you can implement to maintain best practices.

Myth #1. Certification bodies (CBs) must conduct a job-task analysis study (JTA) every 5 years.While this is a fairly common practice, there is no hard and fast timeline to adhere to. The myth of a requirement to conduct JTAs every five years may have stemmed from NCCA accreditation standards[i] which require certifying bodies (CBs) to conduct a JTA as the basis for developing the assessment. International Standard ISO/IEC 17024[ii] requires certification schemes to contain job and task descriptions in the scheme and the CB to provide evidence that in the development and review of the certification scheme, a job or practice analysis is conducted and updated to: identify the tasks for successful performance; identify the required competence for each task; identify prerequisites (if applicable); confirm the assessment mechanisms and examination content; and identify the recertification requirements and interval. Since accreditation is awarded by ANSI and the NCCA for 5 years and the application requires submission of a JTA report, it would appear that conducting a revalidation study at 5 year intervals would be a logical step for CBS to take. That it’s a requirement is the myth. So how often should CBs conduct or revalidate JTAs? Much depends on the job, and how quickly the job description evolves. Changes in specific bits of knowledge can be handled by writing new questions. Thus, for a taxi-driver certification, changes in street names might be covered in the item bank. But what if the advent of GPS changes the degree to which a taxi driver needs to know obscure street names? As the job description changes, the need for a new or revalidated JTA increases. In short, JTAs should be revalidated with enough frequency to ensure the competency requirements being assessed reflect current practice. For some certifications, say food safety inspection, practice may not substantially or quickly change in a short period of time. Therefore, the JTA may be current for a longer period of time. For other CBs, say IT security or medical technology, in which technology advances jobs requirements more quickly, a JTA may have a shorter shelf-life and revalidation studies may need to be conducted at a much shorter interval. Ultimately it is up to the CB to determine the currency and relevance of its competency requirements and scheme, and to schedule JTA studies accordingly. This should also be stated as policy.

Myth #2. Enterprises (legal entities) offering certification may not offer training or education programs.This is a commonly discussed myth among CBs, especially those seeking accreditation. What are the facts? NCCA Standard 3 (2014 edition) requires the separation between certification and any education or training functions to avoid conflicts-of-interest, and ISO/IEC 17024, Requirement 5.2 “Structure of the certification body in relation to training” (2012 edition), sets forth several requirements to safeguard the impartiality of certification practices and decisions when training and certification exist within the same legal entity, including assessing threats to impartiality, demonstrating certification processes are separate from training, not requiring completion of owned training programs or suggesting advantages in doing so, and refraining from examining a candidate if a provider of training for a period of time. Like many myths, then, this one is grounded in some facts. But there is no blanket prohibition on offering training and education programs. CBs reflect many organizational structures; they may be separately incorporated (stand-alone), part of a parent corporation, or sponsored by a professional membership association or society. To reduce conflicts-of-interest, or the appearance thereof, and to maintain impartiality in all matters related to certification, enterprises offering training and certification should separate these operations (think of “church and state”). Some strategies for separating church and state include:

Enterprises may find many opportunities to create revenue streams and to offer conveniences to candidates and certified persons in offering exam prep materials or renewal CEs without compromising impartiality or creating a conflict-of-interest. These opportunities should be stated as policy.

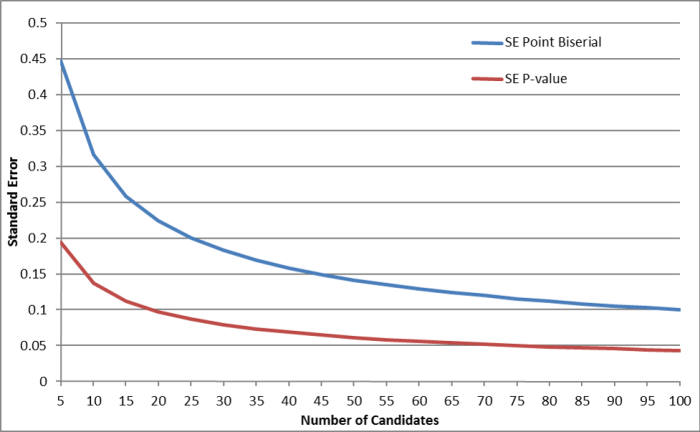

Myth #3. CBs must administer assessments to at least 100 candidates in order to obtain reliable data on item performance.This myth may originate with a good-faith concern that the data you rely on should, in fact, be reliable. Where it’s possible to have larger numbers of candidates (“n”), that is good. Accrediting bodies must understand, however, that some CBs may administer only a few exams. So how does a CB know if it has enough reliable data? While 100 candidates does provide more stable statistics than say 75, 50 or 30 candidates, 100 is not a magic number. I asked my colleague Reed Castle, Ph.D., our director of psychometrics, for a technical perspective. He noted that a good way of evaluating the accuracy or stability of statistics is to look at standard error estimates for p-values (difficulty) and point biserial estimates (discrimination) for different numbers of candidates. The chart below tracks the standard error estimate for items with a p-value of 0.75

Each statistic should be interpreted with its given standard error estimate. Looking at the standard error for the p-value, there is not a dramatic difference in the standard error when the sample size is 50 or 100. The pitch of the decrease in the standard error lines is steepest when samples sizes are less than 30 or 25. Consideration should be given to standard error of any statistic when interpretations are made and p-values appear to be more stable than correlation-based discrimination indices. Working with their psychometric consultants, CBs dealing with small numbers of candidates should develop strategies to mitigate concerns associated with interpreting statistics with small sample sizes. Working with their psychometric consultants, CBs dealing with small numbers of candidates should develop strategies to mitigate concerns with reliability. For example, where a CB with larger numbers may flag items with a point biserial correlation below 0.10 for further review, a CB with smaller numbers may choose to review items with a point biserial correlation below 0.20 to make up for the larger error band around their numbers. The myths discussed in this first installment may have originated from a desire to summarize thoughtful discussions into bite-sized rules. Yes, CBs need to carry out (or revalidate) JTAs periodically; but there is no five-year requirement. Yes, there are issues around training and certification that require care; but there is no prohibition on enterprises being involved in both with proper safeguards. Yes, statistics derived from smaller numbers of candidates require greater care in their interpretation; but they can be used. Certification best practices are based on concerns for fairness, impartiality, and credibility. They cannot and do not, however, ignore the real-life needs and circumstances of certification bodies. Don’t let the myths scare or mislead you. [i] National Commission for Certifying Agencies, Standards for Accreditation of National Certification Organizations (1995); revised in 2007 and retitled Standards for the Accreditation of Certification Programs; revised in 2014. The NCCA is structured under the Institute for Credentialing Excellence (ICE). [ii] ISO/IEC 17024 Conformity assessment—General requirements for bodies operating certification of persons adopted in 2003 and revised in 2012. Administered in the United States by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) Categorized in: Regulatory Power |

||

Comments are closed here.