From the Item Bank |

||

The Professional Testing Blog |

||

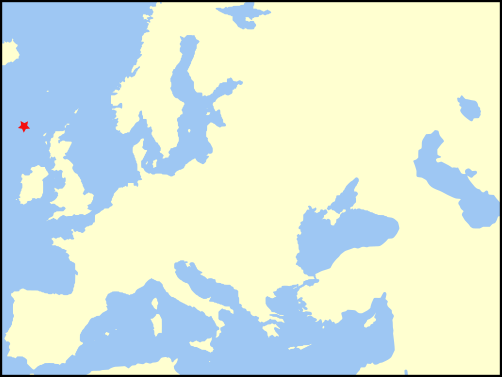

Write Item Variants to Save Money and Improve Test QualityDecember 6, 2016 | |An item variant is simply a new test item that is based on an existing test item. Writing item variants can be a way of saving money while improving test quality and test security. It is good to consider the possibilities and to be aware of the limitations of this undertaking. Variants. Variants can be written in the initial item-writing stage: write an item, then write one or more variations on the item. This is simply a way of getting more items for minimal effort. Clones. Variants can also be written after items have been pilot tested. A small group of subject-matter experts may review the best-performing items on a test for cloning potential. The hope is that the clones will perform as well as the originals—leading to an increase in the number of well-performing items in the bank. There are no guarantees, of course.  Figure 1. Item 101F. Drag the star token into France. Credit: wikimedia.org (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

Figure 1, showing Item 101F, is a fairly obvious example of variant writing for a (fictive) test of basic geographical knowledge. For a quick variant, try Item 101G. “Drag the star token into Germany,” using the same graphic. Item 101S might be, “Drag the star token into Slovenia.”  Figure 2. Item 102F. Drag the star token into France. The token must be fully inside the country. Credit: wikimedia.org (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

Before trying the numerous variants that readily emerge, however, it may be prudent to try testing the knowledge covered in Item 101F in other ways and to see which is best. Figure 2 shows Item 102 F, where the map does not show political boundaries.  Figure 3. Item 103F. Drag the star token into France. Credit: wikimedia.org

And Figure 3 shows another variation, Item 103F, with a map of the world instead of a map of only Europe. In scoring Item 103F, it will be necessary to watch out for (and give credit to) people like me, who would drag the token to Réunion, the overseas region and department of France in the Indian Ocean. Templates. What has emerged out of this experiment with map-based items is a useful tool in item writing: the item model or template. In many but not all contexts, developing and using templates can be an excellent way of generating additional content at lower cost than incurred crafting items from scratch. The brand-new edition of the Handbook of Test Development proffers this example of a template.

Each element is defined and limited. For example, [[AGE]] can be 24, 28, or 32. [[ALLERGY]] can be included or excluded; if included, it will read, “who is allergic to penicillin.” [See Mark J. Gierl and Hollis Lai, “Automatic Item Generation,” in Handbook of Test Development, ed. Suzanne Lane, Mark R. Raymond, and Thomas M. Haladyna. New York: Routledge, 2016. Pp. 410–29.] Templates offer advantages associated with automation (the focus of the article from which this example is taken). For smaller programs, they offer a chance to protect the test, at low marginal cost, from the test-security disadvantages of item exposure. Put plainly, if someone hears about a question about antibiotic choice for a 24-year-old pregnant woman at 5 week gestation with cellulitis, and the test offers up a 28-year old woman at 25 week gestation with left lower lobe pneumonia, the candidate’s unfair advantage over others is minimized. Of course, overreliance on a small number of templates can negate this advantage. (“Oh, there’ll definitely be a question about antibiotics for pregnant women. Study up on that one.”) Multiple-choice questions. Even where there is no set plan to use templates or clone items, openness to variant writing can create efficiencies. For example, a subject-matter expert working on multiple-choice single-response items about New Jersey traffic laws may come across New Jersey Statutes Annotated 39:4-125, which provides that a U-turn is illegal in four circumstances: [1] upon any curve; [2] upon the approach to or near the crest of a grade; [3] at any place upon a highway . . . where the view . . . is obstructed within a distance of 500 feet . . . in either direction; [4] on a highway which shall be conspicuously marked with signs stating “no U turn.” The item writer may compose an item along the following lines: Item 201A. In which of the following circumstances is a U-turn illegal?

A would be the credited response, with the language simplified. B and C are common misperceptions: The final distractor uses an element from the law (500 feet) which may attract candidates who have a vague familiarity with the law but don’t actually know it: The item writer might immediately compose a variant, where the credited response is another of the circumstances listed in the source material: Item 201B. In which of the following circumstances is a U-turn illegal?

And yet another: Item 201C. In which of the following circumstances is a U-turn illegal?

For Item 201C, distractor D should probably be replaced. The fourth obvious item in this set of variants, “Where there is a sign stating ‘no U turn,’” is probably too trivial to test. This method can often be used where source materials or experience provide a list of parallel elements that candidates need to know. Item characteristics. In each of the cases above, it is clear that variants may not have the same item characteristics.

Takeaways. Here are some takeaways from this discussion.

Categorized in: Industry News |

||

Comments are closed here.